Read Dinner With Churchill: Policy-Making at the Dinner Table Online

Authors: Cita Stelzer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #History, #World War II, #20th Century, #Europe, #World, #International Relations, #Historical, #Political Science, #Great Britain, #Modern, #Cooking, #Entertaining

Dinner With Churchill: Policy-Making at the Dinner Table (6 page)

1

. Wilson, “World of Books,” commenting on Roy Jenkins’ life of Churchill,

Daily Telegraph

, 7 June, 2004

2

. Sir Christopher Meyer to the author

3

. Soames,

Mary Clementine Churchill

, p. 260

4

. “In Honour Bound: My Father, Lord Mountbatten”, talk by The Countess Mountbatten of Burma, in

Proceedings of the International Churchill Societies

, p. 5

5

. Bonham Carter,

Winston Churchill as I Knew Him

, p. 16

6

. Skidelsky,

John Maynard Keynes: Fighting for Britain, 1937-1946

, p. 80

7

. Coote,

The Other Club

. Endpapers

8

. www.bbm.org.uk/Savoyhotel.htm

9

. Macmillan,

The Past Masters 1906-1939

, p. 150

10

. Gilbert (ed.),

War Papers

, Volume 3, p. 421

11

. Martin,

Lady Randolph Churchill, The Dramatic Years, 1895-1921

, p. 295

12

. Gilbert,

Winston S. Churchill, Prophet of Truth,

Volume V,

1922-1939

, p. 265

13

. Manchester, William,

The Last Lion

, Volume 2, p. 27

14

. Roberts, Andrew,

Masters and Commanders

, p. 80

15

.

The Washington Post, 27

December, 1941

16

. Gilbert,

Winston S. Churchill, The Stricken World, 1917-1922

, Volume IV, p. 138

17

. Gilbert,

Winston S. Churchill

, Volume IV, pp. 138-9

18

. Kramnick, Isaac and Sherman, Barry,

Harold Laski: A Life on the Left

, p. 1

19

. DeWolfe, Mark (ed.),

Holmes-Laski Letters: The Correspondence of Mr. Justice Holmes and Harold Laski, 1916-1953

, p. 1136

20

. Henderson, Nicholas

The Private Office Revisited

, p. 83

21

. Davies, Joseph E.,

Mission to Moscow

, p. 150

22

. Letter from the 4th Lord Dufferin and Ava. Lord Dufferin added, “I shall ever remember the evening throughout my life”. CHAR 1/232/11

23

. CHAR 1/232/ 7

24

. CHAR 1/242/21

25

. Nasaw, David,

The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst

, p. 418

26

. CHAR 1/254/39

27

. Wyatt,

To The Point

, p. 32

28

. CHAR 1/244/81

29

. Gilbert, email to the author, 19 April 2011

30

. Buchan-Hepburn, Patrick, to Sir Martin Gilbert,

In Search of Churchill: A Historian’s Journey

, p. 304

31

. James Scrymgeour-Wedderburn, quoted in Gilbert,

In Search of Churchill, A Historian’s Journey

, p. 231

32

. Montague Browne, Anthony,

The Long Sunset

, p. 116

33

. Montague Browne, p. 118

34

. In conversation with the author

35

. Soames (ed.),

Speaking for Themselves

, p. 344

36

. Edward Rothstein, “Contemplating Churchill,”

Smithsonian

, March 2005, p. 91

37

. Soames (ed.), p. 259

38

. CHAR 1/386/16

39

. CHAR 1/386/17

40

. CHAR 7/15/103

41

. CHAR 7/15/99

42

. Martin, Ralph G.,

Lady Randolph Churchill

, Volume I, p. 149, from George W. Smalley,

Anglo-American Memories

, 1911

43

. Churchill,

My Early Life

, p. 150

44

. Cooke, Alistair,

General Eisenhower and the Military Churchill

, p. 52

45

. CHAR 1/315/121 and CHAR 1/268/98

46

. CHAR 1/254/40 and CHAR 1/282/66

47

. CHAR 1/315/125

48

. CHAR 1/315/122

49

. CHAR 1/315/123

50

. Cooper,

Trumpets from the Steep

, p. 180

51

. Norwich, John Julius (ed.),

The Duff Cooper Diaries

, 11 January 1944

52

. Letter from Jo Sturdee, later Countess of Onslow, to her family from Hotel de la Mamounia, Marrakesh, Morocco, 7 January 1948. CHUR/ON SL 2

53

. Graebner,

My Dear Mr. Churchill

, p. 78

54

. Gilbert,

Winston S. Churchill, Road to Victory, 1941-1945

, Volume VII, p. 979

55

. Moran,

Winston S. Churchill, The Struggle for Survival

, p. 213

56

. Pawle, p. 344

57

. Colville,

The Fringes of Power

, p. 639

58

. Reported by Elizabeth Olson, “Churchill’s Lifelong Romance With a Feisty Former Colony,”

The New York Times

, 7 February 2004

59

. Cohen,

Supreme Command

, p. 118

*

Close to £7,000 in today’s money.

“It is fun to be in the same century with you.”

1

President Roosevelt to Prime Minister Churchill

W

hen Churchill became Prime Minister in May 1940, he was powerfully aware that his best chance –

probably

his only chance – of not losing the war was to persuade the United States to come in on Britain’s side. But America in May 1940 was in no mood to have its sons fight again in foreign wars, and, in the election in November of that year, President Roosevelt promised he would never send Americans on such a mission.

Churchill also knew of a considerable reservoir of anti-British feeling among two important voting blocs in the United States, the Irish- and German-Americans.

Many Irish-Americans were “instinctively anti-British”

2

and opposed, with a harsh hatred, British rule in Northern Ireland. Joseph Kennedy, a leader of Boston’s Irish community and the American Ambassador to the Court of St. James’s

*

, sent the President several emphatic reports claiming that Britain could not possibly defeat Hitler. And 20,000

German-Americans

rallied at Madison Square Garden in New York in February 1939, in opposition to Roosevelt’s increasing criticism of Hitler’s foreign policy.

All this made it urgent, in Churchill’s view, that he meet face to face with Roosevelt. The two had been

corresponding

on a regular basis for several years but Churchill felt correspondence was no substitute for a face-to-face

meeting

. Harry Hopkins, the President’s closest adviser, had told Churchill on his crucial visit to Britain in January 1941 that the President was also eager for such a meeting.

3

The Prime Minister intended to explain Britain’s situation, persuade Roosevelt to help, belatedly, with the loan – better still, the gift – of destroyers, and pave the way for America’s entry into the war as soon as the President felt it would be politically possible for him to take such a step. Churchill believed, as he wrote to the President, a conference between them “would proclaim an ever closer association and would cause our

enemies

concern, make Japan ponder, and cheer our friends”.

4

Most heartening to Churchill was Hopkins’ news that Roosevelt favoured a meeting. Personally welcome, too, were the gifts Hopkins brought with him from America: “ham, cheese, cigars etc. for the P.M.”,

5

the first of many food

parcels

the Churchills were to receive from the Roosevelts. In Washington, planning for the meeting was top secret: the

Washington press corps was told that the President was going fishing off the Maine coast on board the USS

Potomac

, his presidential yacht. He was then transferred to the USS

Augusta

on the morning of 5 August to sail to

Newfoundland

.

In London, the Prime Minister’s plans were also top

secret

. Colville writes in his diary: “The PM disappeared to Chequers and I shall not see him for a fortnight as he is very shortly off on a historic journey (Operation Riviera!).”

6

On 3 August, Colville notes, Churchill took the train “north with a retinue Cardinal Wolsey might have envied”.

7

The Prime Minister’s railway dining car

The Foreign Office diplomat, Sir Alexander Cadogan, records in his diary that, on board the Prime Minister’s

private train, he and Churchill had a “V. good lunch –

tomato

soup, sirloin of beef (in unlimited quantities and quite excellent), delicious raspberry and currant tart”.

8

On 4 August, Churchill boarded the

Prince of Wales

, at Scapa Flow, the deepwater harbour of the Atlantic fleet in the Orkney Islands off Scotland’s far north-eastern coast.

The North Atlantic seas were rougher than usual, and the destroyer escorts were alert to U-boats, whose presence in the area had been confirmed. An erratic course was taken in an attempt to evade the enemy. Churchill, however, was not worried and enjoyed the trip. His mind was on the work to be done to prepare for the meeting with Roosevelt. But he had also planned his leisure time, bringing along his favourite films. On the first night out, he and his staff watched

That Hamilton Woman

(about Lord Nelson’s mistress, a story of British defiance in the Napoleonic Wars, appropriate for a wartime sea voyage), and

Pimpernel Smith

, a 1941 remake of the 1934 movie,

Scarlet Pimpernel

, based on Baroness Orczy’s swashbuckling novel about a dashing hero who saved French aristocrats from the revolutionary guillotine. In the updated version, Leslie Howard (who also produced) smuggles Nazi victims out of Germany.

Churchill read what he cites as “Captain Hornblower R.N.” by C.S. Forester, and cabled his Minister of State for the Middle East, Oliver Lyttelton, who had recommended it: “Hornblower Admirable”. This created a minor flurry amongst senior officers on board as to what possible

military

or naval operation had the code name “Hornblower”. Throughout the trip, the Prime Minister clearly enjoyed

himself

, even though the crew were continually anxious about the U-boat threat.

Planning for meals had been meticulous: the ovens of

the

Prince of Wales

could bake 1,500 loaves of white bread; and to its distinguished passengers its galley challenged “

comparison

with the kitchens of The Ritz”.

9

Provisions aboard were “ceiling-high”, including chocolates and cigarettes. Cadogan, whose diaries contain more comments on food than do those of any of his contemporaries, tells us: “We took on a cargo of grouse in Scotland, and we have some very nice beef. Masses of butter and sugar”.

10

The grouse, a Churchill

favourite

11

, were available because, it seems, the grouse season was opened earlier than usual to allow shooting to supplement rationed foods. The butter and sugar were especially

appreciated

since they had been rationed since January 1940.

On 6 August, Cadogan again records a memorable meal. The ship was in mid-Atlantic, in dense fog, awaiting a new flotilla of destroyers that had set out from Iceland to guard the convoy. Harry Hopkins was on board one of the ships in the flotilla, hitching a ride home after his visit to Stalin. Hopkins had brought along

a tub of admirable caviare, given him by Joe Stalin. That, with a good young grouse, made a very good dinner. As the PM said, it was very good to have such caviare, even though it meant fighting alongside the Soviets to get it.

12

When Hopkins, who years earlier had had two-thirds of his stomach removed due to a cancer, prudently refused a second brandy, the Prime Minister said, “I hope that, as we approach the US, you are not going to become more temperate.”

13

It was another instance of Churchill’s

contribution

to the myth-making and humour about his drinking habits. Hopkins recorded Churchill’s high spirits about his forthcoming meeting with the President: “You’d have thought

he was being carried up to the heavens to meet God.”

14

On 9 August, the

Prince of Wales

sailed into Placentia Bay, Newfoundland. An eager Churchill and his staff then crossed by barge to the USS

Augusta

, where the Prime Minister handed the President a personal letter from King George VI, smiled, shook hands and lit his signature cigar. The President lit his cigarette and to Churchill’s

delight

, invited him to remain aboard for a tour and a private lunch. That evening, the President invited the Prime Minister and his party to return for a formal dinner, at which broiled spring chicken, vegetable puree, spinach omelettes, candied sweet potatoes, hot rolls, currant jelly, mushroom gravy, tomato salad and cheeses were served. Dessert was a choice of ice-creams, cupcakes or cookies, or all three for the

food-rationed

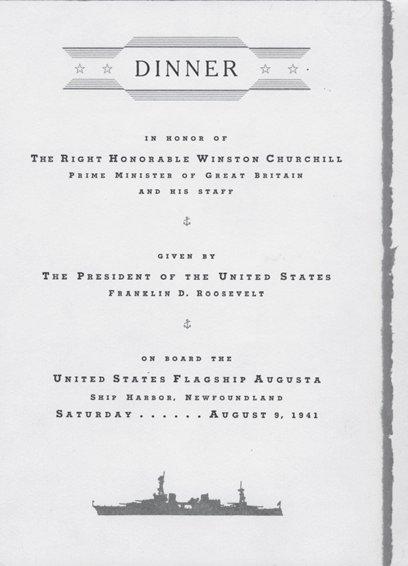

British guests. “In place of liqueurs, they were offered coffee, tea, mints …”

15

Surely wines were served, as the presidential party was not subject to a dry Navy rule, but they are not listed on any menus or mentioned in letters or diaries.

Churchill had spent many hours devising a Divine Service for the following day, Sunday, 10 August, to be celebrated on board the

Prince of Wales

with Roosevelt and crew

members

from both ships. Ever alert to possibilities that would enhance what came to be called the special relationship, the Prime Minister instructed members of his staff not to stand at attention during the church parade but to mingle freely and informally with their new American friends.

It was a very moving occasion. Churchill chose two hymns and asked the President to choose another. Churchill chose “O God Our Help in Ages Past” and “Onward, Christian Soldiers”. The President chose his favourite, “Eternal Father, Strong to Save”, the official US Navy hymn,

sometimes also sung on Royal Navy ships (and which was played at Roosevelt’s funeral at Hyde Park, New York). British and American officers and seamen – some 250 men in all – stood together during the church service, which was jointly conducted by the chaplain from the

Prince of Wales

and the chaplain of the US Fleet.

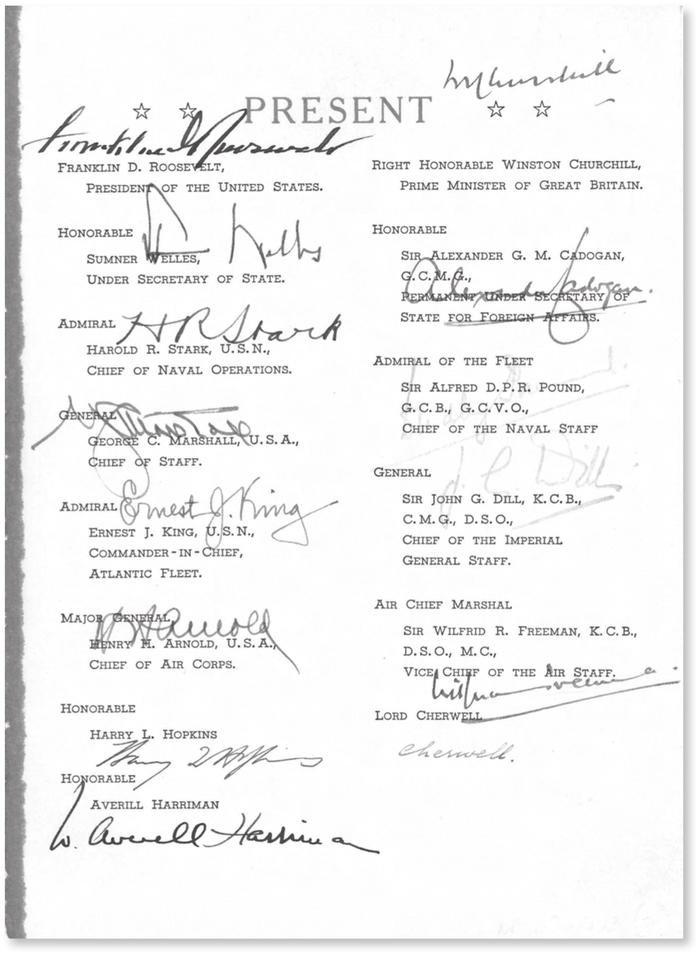

President’s dinner for the Prime Minister aboard the

Augusta,

9 August 1941.

the guests.