Read Dinner With Churchill: Policy-Making at the Dinner Table Online

Authors: Cita Stelzer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #History, #World War II, #20th Century, #Europe, #World, #International Relations, #Historical, #Political Science, #Great Britain, #Modern, #Cooking, #Entertaining

Dinner With Churchill: Policy-Making at the Dinner Table (8 page)

*

The official title of the US Ambassador to the United Kingdom.

C

hurchill never missed an opportunity to confer with key American policy-makers in his tireless effort to

enlist

the United States in Britain's struggle for survival. On the fateful evening of 7 December 1941, he was dining at Chequers with American Ambassador John “Gil” Winant; Averell Harriman (Roosevelt's Special Representative in the UK), and Harriman's daughter, Kathleen (whose birthday it was); Pamela Churchill, (the Prime Minister's

daughter

-in-law); his Principal Private Secretary, John Martin; and Commander “Tommy” Thompson, his ADC.

Churchill was in this distinguished company when Frank

Sawyers, his valet, entered the dining room with a small portable Emerson radio that Harriman had brought with him as a gift from Harry Hopkins.

3

The BBC news bulletin was reporting the devastating surprise Japanese attack on the US naval base at Pearl Harbor. Churchill immediately asked Winant to telephone Roosevelt for confirmation, and just as quickly decided to travel to Washington, both to offer support â “We are all in the same boat now,”

4

the President told the Prime Minister â and to promote his own strategy for prosecuting the war.

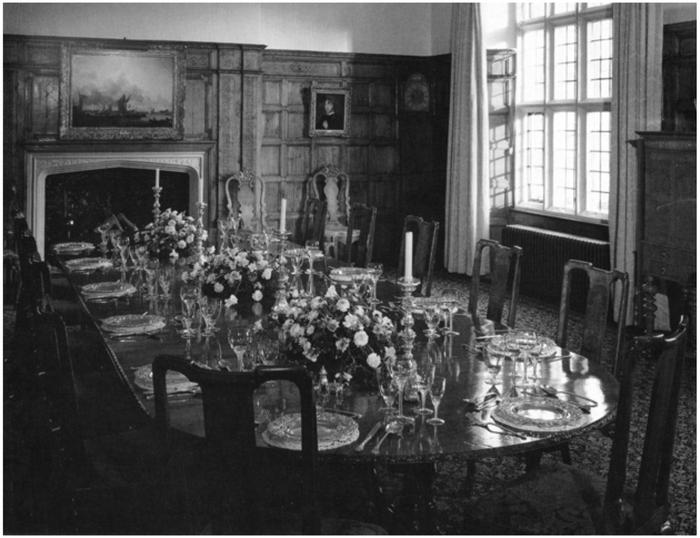

Chequers dining room

The following day, the Japanese attacked the British

colony

of Malaya and on 11 December, Germany declared war on the United States. Britain and the United States had

become

allies in what was clearly going to be a long war against two strong enemies, Germany and Japan. Because Roosevelt

was under substantial Pacific First pressure to avenge the attack on Pearl Harbor, Churchill feared that the war against Germany would be subordinated to an American war against Japan and that the Lend-Lease material would be diverted from Britain to that effort in the Far East.

As always, Churchill believed he could be most effective in a face-to-face meeting. Once ensconced in the White House, he would argue for the joint overall strategy â Europe First â he was convinced would win the war.

Arranging this meeting was no easy thing. Such an

extended

transatlantic visit needed the approval of both the King and the Cabinet, and an invitation from the President. Churchill had little difficulty obtaining the sovereign's

approval

. But the Cabinet was another matter.

The Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, then on his way to meet Stalin, joined his Cabinet colleagues in opposing Churchill's visit, arguing that Britain's Prime Minister and its Foreign Secretary should not be away from London and the House of Commons at the same time. But neither Eden nor the War Cabinet could dissuade the Prime Minister from his view that telegrams and phone calls were no substitute for personal contact. Oliver Harvey, Eden's Principal Private Secretary, noted in his diary:

Really the PM is a lunatic: he gets in such a state of

excitement

that the wildest schemes seem reasonable. I hope to goodness we can defeat this one. AE believes the Cabinet and finally the King will restrain him, but the Cabinet are a poor lot for stopping anything.

5

In Washington, enthusiasm for a Churchill visit was equally muted. Influential congressional supporters of

General Douglas MacArthur favoured a Japan-first strategy. Nor was the President's wife alone in Washington in viewing Churchill as an unreconstructed “old imperialist” trying to drag the United States into a war that would restore Britain's empire. The President, reluctant to receive the Prime Minister, enlisted the aid of the British Ambassador, Lord Halifax, to persuade Churchill to stay at home. Roosevelt told the Ambassador he was worried about Churchill's security, and suggested a meeting in Bermuda at a later date. Neither fears for his safety, nor the prospect of a meeting at some later â perhaps much later â date could dissuade Churchill from

setting

sail for America as soon as possible. The Prime Minister set aside the doubts of some of his Cabinet, confident that the potential effectiveness of his personal diplomacy would secure Britain's urgent national interest to give Hitler no

respite

in Europe. Churchill's greatest fear was that the Nazis would defeat the Soviet Union and then invade Britain.

The President's uncertainty about the visit from the Prime Minister was reflected in cables he, or perhaps members of his staff not eager to expose the President to the Prime Minister's persuasive powers, drafted for transmission to Churchill: “I would like to suggest delay ⦠full discussion would be more useful a few weeks hence ⦠I suggest we defer decision on your visit for [about] one week.” In the event, the cables were not sent, and Churchill and Roosevelt spoke over a radio telephone link later that day. Churchill prevailed. The President finally cabled Churchill: “Delighted to have you here at White House.”

6

For security reasons conversations were never about grand strategy. Ruth Ive, who monitored and, when talk turned

to sensitive areas, censored transatlantic calls between the President and the Prime Minister, noted that “Churchill would sometimes describe the excellent dinner he had just eaten to the somewhat surprised President”.

7

The invitation to stay at the White House certainly suited Churchill, as he wanted to spend as much personal time as possible with Roosevelt, with every opportunity to practise the dinner-table diplomacy in which he had such confidence. Far better than staying at the British Embassy or Blair House, the presidential guest house, where interruptions would be inevitable.

On 12 December, Churchill boarded his special train at London's Euston Station on his way to the Clyde. For

security

reasons, the story had been put out that Lord Beaverbrook was sailing, and that Churchill was at the train station

merely

to see him off. Beaverbrook “had his private saloon on the train, and had a dinner party there before the train started”.

8

Churchill and his party then embarked on the battleship

Duke of York

, sister ship to the

Prince of Wales

on which he had sailed to meet Roosevelt the previous August. (The

Prince of Wales

had been sunk by the Japanese, north-east of Singapore, a few days earlier with the loss of many lives,

including

Admiral Tom Phillips, a friend of Churchill's.) While on board the

Duke of York

, Churchill telegraphed birthday wishes to Stalin, who was 63 on 21 December. Churchill had celebrated his 67th birthday three weeks earlier.

The transatlantic voyage took ten days. Churchill

described

it to his wife as “⦠unceasing gales ⦠No one is allowed on deck, and we have two men with broken arms and legs ⦠Being in a ship in such weather as this is like

being in prison, with the extra chance of being drowned”.

9

Commander Thompson described it also: “Of all the

journeys

which the Prime Minister was destined to make during the war few rivalled this first voyage to America for sheer discomfort.”

10

Nevertheless, Beaverbrook joked that he “had never travelled in such a large submarine”,

11

and Churchill wrote to his wife: “We make a friendly party at meal times, and everyone is now accustomed to the motion.”

12

Churchill's insistence on maintaining his usual habits was unaffected by the turbulence. At one point, the ever-present Sawyers rushed to the bridge to ask Captain Harcourt for help. “The Prime Minister doesn't like the ship's water, and I've run out of white wine.”

13

Presumably, the Captain had extra wines aboard for just such emergencies.

Churchill, as usual, devoted himself to work, albeit

following

his eccentric daily habits. He told Clementine, in the same letter, of his routine:

I spend the greater part of the day in bed, getting up for lunch, going to bed immediately afterwards to sleep and then up again for dinner. I manage to get a great deal of sleep and have also done a great deal of work in my waking hours.

14

The numerous memoranda Churchill wrote while on this sea voyage included: “Future Conduct of the War”; “US troops to Northern Ireland”; “Re-establish France as Great Power”; “The Pacific Front”; “Proposed strategy for 1943 and a possible landing in Europe”.

15

He also read and considered Eden's reports from Moscow on his meetings with Stalin, and other staff reports from London â a full plate indeed. Also on Churchill's mind was preparing what he would say to the President.

On 22 December, Churchill, dressed as at Placentia Bay in a navy pea jacket and blue yachting cap, disembarked at Hampton Roads, at the lower end of the Chesapeake Bay. Insisting that there was not a minute to lose, he was flown up the Potomac to the new National Airport in the capital, where the President greeted him on the tarmac. Together, they drove to the White House. (The others on Churchill's staff were taken by private train to Washington, where they were served hard-boiled eggs, salad and fruit.

16

) Both

politicians

were aware of the perils they faced, aware of the symbolism of their meeting and eager to project confidence and determination â witness the President's jauntily angled Camel in his cigarette holder and the Prime Minister's

ever-present

cigar, which both well knew cartoonists had made a symbol of their imperturbability and steadfastness.

Churchill lived at the White House for the next three weeks. It was the first time in the long history of Anglo-American relations that a British prime minister had lived at the White House during wartime and probably â with the exception of Harry Hopkins â the only time that a non-family member, and a foreigner at that, was welcomed for such an extended period.

Both parties were alert to possible differences, concerned about what the other would think and, more worrying, might demand. Brigadier (later Sir) Leslie Hollis, who was with Churchill, wrote:

The Anglo-American alliance was still untempered steel. The Americans were reeling under the disaster of Pearl Harbor, and possibly a little nervous that the war-tried British might try to tell them what to do. We, on the other hand, were anxious to show that we had no desire to act as

senior partners in the new-formed alliance, but as equals. We had no pattern to guide us â¦

17

At the White House, domestic planning was chaotic:

because

of the secrecy surrounding Churchill's transatlantic voyage, Roosevelt's wife, Eleanor, had not been told until the last minute that the Prime Minster would be her guest over Christmas, usually a family time. She was surprised â even angry â when her husband had asked her whom she had invited for Christmas dinner, as never before had he been interested in her guest lists. Early on the day of Churchill's arrival, the President told his wife and staff to arrange dinner for twenty that night, a dinner that would include the Prime Minister of Great Britain. An old friend of Eleanor, Mrs. Charles Hamlin, watched as Churchill arrived, and recalled that he “wore a knee-length double-breasted coat, buttoned high, in seaman fashion. He gripped a walking stick with an attached flashlight for the purpose of navigating London blackouts. He reminded me of a big English bulldog who had been taught to give his paw”.

18

Time

magazine said Churchill “swept in like a breath of fresh air, giving Washington new vigour, for he came as a new hero”.

19