Read Dinner With Churchill: Policy-Making at the Dinner Table Online

Authors: Cita Stelzer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #History, #World War II, #20th Century, #Europe, #World, #International Relations, #Historical, #Political Science, #Great Britain, #Modern, #Cooking, #Entertaining

Dinner With Churchill: Policy-Making at the Dinner Table (2 page)

T

his is a book about an extraordinary man deploying an extraordinary method of representing his nation’s

interests

and, in his view, those of the English-speaking peoples. Winston Churchill was one of those rare men who made history, most notably in his decision in 1940 that Britain would not strike a deal with Hitler but would fight on.

Churchill’s definitive biographer, Sir Martin Gilbert, and others have chronicled the techniques used by Churchill to develop and persuade others to accept his strategic vision for fighting the war. This book focuses on just one: his use of dinner parties and meals to accomplish what he believed

could not always be accomplished in the more formal setting of a conference room.

Downing Street dining room

It is a story of both successes and failures: success in persuading the President of the United States after Pearl Harbor to adopt a “Europe first” strategy despite the fact that America had been attacked not by Germany but by Japan, and that public opinion favoured retaliation across the Pacific rather than the Atlantic; failure in his inability to persuade another American president to meet with the Soviet Union’s leaders in an effort to resolve differences that resulted in the Cold War.

Churchill had no illusions about the limits of personal diplomacy. As he told the House of Commons:

It certainly would be most foolish to imagine that there is any chance of making straightaway a general settlement of

all the cruel problems that exist in the East as well as the West … by personal meetings, however friendly.

1

Churchill was also well aware that his success depended not only on the detailed planning that went into his dinner parties, or on his ability to make a case for his strategy of the moment. It depended, also, on facts on the ground. In late December 1941, when he visited Franklin Roosevelt for an extended round of informal and formal meetings, British troops were carrying the burden of the fight against Hitler, while the United States, so soon after Pearl Harbor, had yet to deploy a single soldier in Europe. But in the final phases of the war, by the time of the meetings of the Allies in Yalta and Potsdam, the Soviet Union and the United States were clearly the dominant powers, and there was little Churchill could do to affect the future of Europe. When he met with President Dwight Eisenhower and his implacable Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, in 1953 in Bermuda, Britain was as close to financial ruin as any nation could be, struggling to sustain its contribution to the battle against communism and the maintenance of world order.

Sadly, it is also the case that the man who became Prime Minister in May 1940 at the age of 65, and had seen his nation through the most desperate period in its history, was by the time he attempted to appeal to President Eisenhower no longer as acute as he had been a decade

earlier

. The physical strain of wartime leadership as Churchill practised it – hands-on control of all details, numerous

gruelling

trips – the inevitable effects of age and the diminished condition of Britain combined to reduce the effectiveness of such persuasive powers as Churchill clearly retained.

Any reasonable assessment of Winston Churchill’s

dinner-table

diplomacy must conclude that he won more than he lost. At numerous dinners at the White House he did help to persuade the Americans to throw their massive industrial and military power against Hitler, leaving Japan for later. He did use the occasion of a private meeting with Joseph Stalin to suggest a division of spheres of influence in Europe which saved Greece from communism. He accepted that he could not persuade Stalin to cede what his armies had conquered in Eastern Europe, but then again, neither could Franklin Roosevelt nor Harry S Truman. And he could not persuade Eisenhower, after Stalin’s death, to seek a settlement with the Soviets, or at least to see if one might be within the reach of the West. Even so, his personal diplomacy, deployed en route to Fulton, Missouri in 1946, combined with Truman’s secret information eventually contributed to Truman’s

willingness

to adopt policies that reflected Churchill’s definition of the post-war geopolitical situation after the Iron Curtain descended on Europe.

It is clear that Churchill used the informal setting of dinner parties to enhance his efforts to shape the future of Europe and the post-war world. The eminent military

historian

Carlo D’Este sums up Churchill’s efforts:

Not a single moment of his day was ever wasted. When not sleeping he was working, and whether over a meal or

traveling

someplace, he utilized every waking moment to the fullest.

2

It occurred to me that it might be interesting to look into the details of the many dinners that Churchill organised and attended. His curiosity led him to want to know, first-hand, what his negotiating partners were like; his self-confidence

led him to believe that face-to-face meetings, the less formal the better, were the perfect occasions in which to deploy his skills. And his fame enabled him to bring together the best, brightest and most important players of his day.

Where better to get to know an ally or opponent, where better to display his charm and breadth of knowledge than at a dinner table? Where better could Churchill rally political supporters, and plan strategy and tactics, than at a working dinner?

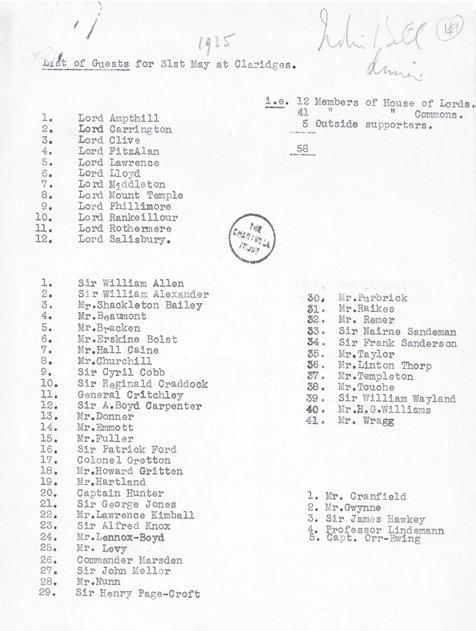

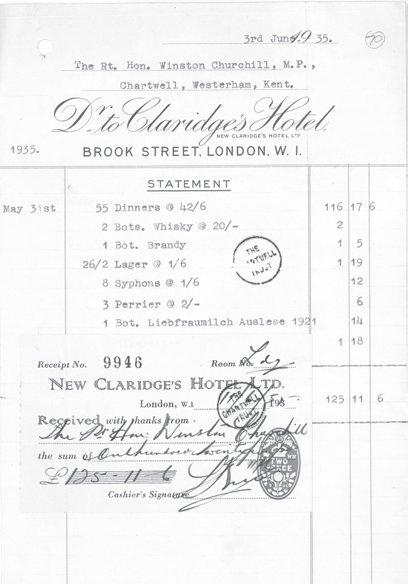

In the spring of 1935, Churchill, who was then “in the wilderness”, having been out of ministerial office for six years, planned a dinner for those, like himself, who opposed the contentious India Bill then making its way through Parliament. Fifty-five MPs and Lords attended. One

thank-you

letter to Churchill pointed out that the dinner, held a week before the forthcoming vote, had helped “not only to steady the troops for next week but to form a rallying point for our Conservative and Imperial thought”.

3

Churchill paid the £125 11 shillings and 6 pence bill from Claridge’s personally.

After losing this legislative battle, Churchill resorted to dinner-table diplomacy to make the best of a losing hand. He invited one of Gandhi’s supporters, G.D. Birla, to lunch at Chartwell, his beloved country house, “as a gesture of reconciliation”, greeting him in the garden in a workman’s apron and sitting down to lunch, very informally, without removing the apron. Birla was charmed, reporting back to Gandhi that it “had been one of my most pleasant

experiences

in Britain”.

4

At his dinners and lunches Churchill sought to convey information as well as to receive it and, in the case of the King, to discharge his obligation as the King’s First Minister.

Churchill established a regular lunch, called his Tuesdays, to report all the details in the progress of the war to King George at Buckingham Palace. The first such lunch was on 10 June 1940, exactly a month after he became Prime Minister. Churchill shared with the King the results of the Enigma intelligence he made known to very few people, and the military details of the war and discussed military and staff appointments with his sovereign. The lunches were private, just the two men – no servants – serving themselves, buffet-style from a sideboard.

Digesting the India Bill

During the war, the Prime Minister also invited the King to Downing Street for dinners in the basement dining room, introducing him to British and American military

personnel

, and to members of the Coalition Cabinet. At Churchill’s suggestion, these dinners are commemorated on an

impressively

large plaque still set into the wall in the Downing Street basement, now used to house the secretarial staff:

In this room during the Second World War his Majesty the King was graciously pleased to dine on fourteen occasions with the Prime Minister Mr. Churchill, the Deputy Prime Minister Mr. Attlee and some of their principal

colleagues

in the National Government and various high

commanders

of the British and United States forces. On two of these occasions the company was forced to withdraw into the neighbouring shelter by the air bombardment of the enemy.

The menu at a small lunch there on 6 March 1941 was: “Fish patty, tournedos with mushrooms on top and braised celery and chipped potatoes, peaches and cheese to follow. The drinks were sherry before lunch, a light white wine

(probably French) during lunch and port and brandy

afterwards

as well as coffee. Saccharin as well as sugar was on the coffee tray”.

5

A reinforced dining room fit for a king

Churchill’s relationship with the King deepened as the war went on and they enjoyed each other’s company. At one lunch in 1943, the King surprised the Prime Minister by serving him a special French wine from 1941, but would not reveal how he was able to obtain a bottle from what was then behind enemy lines.

6

Mrs. Churchill remembered that at one lunch with the King and Queen, the Prime Minster had “tried to interfere with the menu” but she was able to stop him and recalled that the lunch turned out very well indeed.

7