Authors: Kerry Greenwood

Tamam Shud (3 page)

Eight large envelopes and one small envelope

One piece of light cord

One scarf

One shirt without a name tag

One yellow coat shirt (a shirt with an attached collar)

Two airmail stickers

One rubber (meaning an eraser)

One front and one back collar stud

Toothbrush and paste

So what can we make of these pitiful relics? As my father said, Somerton Man had good taste in clothes,

though tending towards the gaudy. His case contained only enough for a few nights, a week perhaps. No extra shirts, for a start. This was a cleanly man who changed his clothes every day. He must have owned more shirts or what was the point of having more than one tie?

The most exciting discovery in the suitcase was the orange Barbour thread, which was not sold in Australia. Identical thread had been used to repair the pocket of Somerton Man's coat. Waxed thread is not usually used to mend clothes: it must have been an emergency repair, intended to last only until he could lay hands on a seamstress. It seemed unlikely that the Barbour thread in the suitcase and the Barbour thread in Somerton Man's coat were not connected, so the suitcase probably belonged to Somerton Man. Also, the clothes are his size and the slippers would fit his feet.

And some of the garments in the suitcase actually had labels with a name on them. There must have been cautious rejoicing amongst the exasperated police at that point, although they should have known it was too good to be true. The name, written on a singlet, a laundry bag and a tie, was T. Keane. Or possibly T. Kean. The call went out and a local sailor named Tom Reade was said to be missing. Was Somerton Man perhaps Tom Reade?

But when Tom Reade's shipmates viewed the body, they all said that it was not their Tom Read. Meanwhile widespread searches through maritime agencies had

revealed that no one was missing a T. Keane or Kean. Rats (or the equivalent), one can hear the law enforcement persons say.

The clothes were also marked with drycleaning or laundry marks, which were applied to clothes when they were submitted for cleaning, so that the cleaner could identify them if their tag was lost. These marks were 1171/1 and 4393/7 and 3053/7 but extensive searches of laundries and drycleaners found no one who used those combinations of numbers. Notably, the only marked clothes in the suitcase, which also had a name on them were those where the name could not be removed without destroying the garment â for instance, the singlet, where the name was written inside the band in indelible ink. And it also seems reasonable to assume that Somerton Man left the names where they were because he knew that he was not Tom or any other Kean(e) â not Terence, Tipton, Trevelyan and so on. Besides, it is unusual to buy second-hand underwear. Even if you are very poor, you usually save to buy new knickers. I speak from personal experience.

So why did Somerton Man have T. Keane's laundry bag? It's another mystery: this matter has a plethora of them. Tom Keane was said to be a sailor, so the laundry marks may relate to a ship's laundry. Somerton Man might have been on the same ship as Tom Keane and picked up his laundry by mistake â although that

doesn't explain the tie, given that ties are drycleaned, not laundered. Somerton Man might also have deliberately swapped his own marked garments for similar garments belonging to Tom Keane, who would probably not mind, as long as he got a singlet of some sort, although it was not kind to nick Tom Keane's tie as well. If the name on Somerton Man's own tie was a problem, he could have adopted the solution used when I was a child â blacking out the old name in Indian ink and writing your own beside it. Indian ink is really black.

The clothes were all examined by experts. The police called in a tailor, Hugh Possa of Gawler Place, who explained that the careful construction of the coat, with feather- stitching done by machine, was definitely American, as only the American garment industry used a feather stitching machine. So the clothes were very high value schmutter indeed. Such coats, the police were informed, were not imported. They were made up to a certain stage and then could be quickly tailored to the figure. The sort of thing which might be bought by someone who wasn't staying long in port, but was willing to pay a high price for a beautifully made, hand-finished suit. From which he then removed the label.

Somerton Man also had very snazzy taste in nightwear. His pyjamas and gown are brightly coloured, and his felt slippers are red. My father's taste also tended to the bright. I have a Hawaiian shirt of his that can only

be viewed through dark glasses. Such things were a mark of a free spirit. Men of the time might have considered these garments to be outrageous, even effeminate. That is another thing we will never know.

It is interesting that there was sand in the cuffs of the trousers in the suitcase. Unfortunately, although its presence was noted, the sand was not examined or analysed. In the same cuffs were stumps of barley grass, which is the stuff that grabs any passing cloth and screws itself into the weave. (It has to be cut out of cat's fur and children's hair, because it's as adhesive as bubble gum.) Everyone always assumes that Somerton Man had just arrived in Adelaide on the day he died but the sand in the cuffs might mean that he had been to Somerton Beach before he arrived at the station and maybe changed his clothes afterwards. Or was he landed, perhaps, with his suitcase, on another beach, brought ashore by dinghy from a ship, walking the last little way across the sand and hoping â successfully, as it happens â to avoid notice? After which, a snappy dresser might have folded those trousers into his suitcase, still with sand in the cuffs, and put on fresh ones.

Somerton Man's shoes were clean, however, and looked to have been recently polished. He can't have walked ashore in them. Seawater does very nasty things to leather shoes. Did he tippytoe barefoot through the waves with his shoes in his hand? Did he put them on

when his feet dried and stop at the shoeshine stand near the station, after he had his wash and checked his suitcase? My father said that the Central Station shoeshine man did a wonderful job, even on army boots. If so, Somerton Man must have paid him with his very last tuppence in the world.

Last but not least, my father, drawing on his experience as a wharfie, told me that the stencilling brush, the modified knife, the screwdriver, pencils and the scissors found in Somerton Man's suitcase were all part of a cargo master's equipment â the stencilling brush for marking cargo and the other items for cutting or replacing seals. Cargoes were more fun back in those days. Instead of containers, which are anonymous and boring, balanced for weight, there were bales and sacks and boxes and crates, all carried by men out of ships and along gangplanks. Hard labour.

My father always said that 120 pounds of grain was a lot easier to carry than 90 pounds of potatoes. I couldn't carry 120 pounds (or 50 kilos) of grain if my life depended on it but they did, for eight hours, up and down and along, from the hold to the deck to the truck or railway flatbed. Sometimes the bales and sacks and boxes and crates were taken up to the deck and swung out on cargo nets. That's why wharfies had cargo hooks, formidable little hand weapons, used for handling cargo, cleaning fingernails and settling differences of opinion.

Working on the docks was called âbeing under the hook' because another hook was holding up those nets, attached to a derrick, or crane, and handled with extreme care and delicacy.

There were some lovely cargoes. My favourite was the circus. One day a monkey stole Mickey Bower's woolly hat and had to be bribed with a hastily acquired banana to give it back. Thereafter, Mickey's gang was always of the opinion that the hat had looked better on the chimp. Most of the circus animals were in stout iron cages that could be swung down gently to the dock but the elephants had to walk onto a cargo hoist.

You can sling a horse, because even if it struggles, it can't actually get out of the sling, but an elephant is another matter. There was a three-inch gap between the ship and the platform at the top of that hoist and I saw the elephant's trunk go down and feel along the gap. She clearly thought: not a chance. That's empty air under there. A horse can be pushed but even with six men shoving, when an elephant decides she is staying put, then put is where she stays. That elephant wouldn't allow herself to be transported until an astute handler led the baby elephant onto the hoist by its little trunk and it got down all right. Even then, it was a struggle to make sure she didn't leap after the baby. Wharfies hated animal cargoes.

I used to love watching my father handle horses. The racehorses came over from New Zealand on our ships,

the Union Steamship Company. My dad always got the job of soothing them so that they didn't have the vapours and break something valuable, like their precious legs. A hysterical horse is a frightening thing, like a revolving chainsaw with hoofs that screams a lot. But they always behaved for my father because he had a secret weapon â a box of those XXX peppermints. They were round, flat, white tablets, so strongly flavoured that just licking one of them destroyed 55 per cent of your tastebuds and made your eyes gush water. Horses adored them. As long as his peppermints held out, even the stroppiest stud would follow my father anywhere.

Some racehorses gave no trouble. The beautiful grey, Baghdad Note, was as tame as an old farm horse. On the other hand, one of the most splendid chestnuts I have ever seen decided to improve his chances of another peppermint by biting off my father's vest pocket with the box in, luckily not taking any of my father with it. I had been reading about those flesh-eating horses in Greek mythology and I was glad that the Union Steamship Company hadn't had to transport them to Diomedes because I knew who would have been leading them out of their loose box.

Cargoes. Boxes and crates and sacks and bales and cases, all marked with their ports of exit and entry, all carefully stowed in the holds of the ship, so that they could be removed in order. Stowage was an art form then.

A ship is not like a truck, with a low centre of gravity moving in one direction along a flat surface. It floats in an unstable medium and therefore it has to balance or the ship will cease to float. Unsecured loose cargo can punch right through the side of a vessel in heavy weather.

As a result, the position of cargo master was a skilled and responsible one, requiring a sound practical knowledge of statistics, meteorology and physics, and a talent for organisation. He kept the chart of the ship on which every stowage was marked. A cargo master has to be a concrete thinker. Otherwise, he and a lot of other people are going to get very wet. If Somerton Man was a cargo master, as my dad suspected, all of this would have been true of him. There is other evidence to suggest that he might have been a seaman of some sort and a cargo master, who would not do manual labour, might well have Somerton Man's unmarked hands and unbroken nails.

Which brings us to the body itself and what everyone made of it.

Chapter Two

What, without asking, hither hurried whence?

And, without asking, whither hurried hence?

Another and another Cup to drown

The Memory of this Impertinence!

The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

, stanza 30

Somerton Man, in extremis, was five feet, eleven inches tall, which is 180 centimetres. He had grey eyes, also called hazel â admittedly a fugitive colour â and blond to reddish hair, greying at the temples. He was healthy, well-muscled and clean, with manicured fingernails and toenails. He was uncircumcised. His legs were tanned. His toes were unusual, forced into a wedge as though he habitually wore tight, pointed high-heeled boots, like a stockman or a dancer or a person willing to suffer to be beautiful. His legs were tanned, in the manner of someone who worked in shorts, and he had what they called âbunched' calf muscles, as seen in people who walk a lot, run long distances, dance or bicycle.

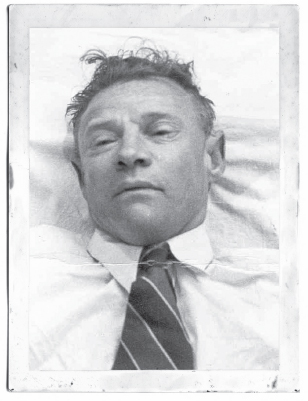

The easy smugness of death. The face that launched a thousand theories. The Somerton Man passed into mystery, taking all his secrets with him.

Courtesy Gerald Feltus

.

I examined the calf muscles of many of my friends, in itself a fascinating if unscientific exercise. (None of them wear high heels, by the way. The definition of high heels in 1949 Adelaide appears to have been about two inches and a riding boot has a two-inch heel so the boot doesn't slip through the stirrup iron.) The bunched calf muscles, which look so good in trunk-hose, belonged to a middle distance runner, three medieval dancers, five bicyclists, several inveterate hikers, a rock-climber, a mountaineer, a rider and one ballet dancer, who had calf muscles like rocks. Somerton Man may have followed one â if not all â of these occupations, although he was probably not a ballet dancer. (Only because he was too old, I hasten to add.) Of course, if he was a cargo master, he would have had to walk miles every day, around decks and up and down companion ways, all day.

Somerton Man's fingerprints. Despite all the cross-checking of police records, no trace of the man's identity could be found.