Of Beetles and Angels (2 page)

At the time, we were furious. But in retrospect, I feel no anger. How can I feel ill will toward Ahferom when I know that soon after, he joined one of the Ethiopian liberation movements? And that later, he joined the long list of senseless casualties, able to survive our crazed dog but not his own countrymen?

Umsagata had no paved roads, so it didn’t attract many cars. We walked or ran everywhere we went.

One time, though, a giant tractor pulled up. It was unlike anything we had ever seen. Its wheels were the size of small adobes!

After a while, the owner got out and entered a home. We ran over to inspect the tires, wondering if what we had heard was true: that if you took a sharp stone and applied pressure to the tire’s little air nozzle, you could empty out all of the air.

We grabbed little stones and pushed eagerly. Sure enough, the air shot out of the tire like lava from a volcano.

The owner shot outside, shaking his fists in fury. We bolted. For we knew that no tire pumps could be found anywhere nearby. And who wants to be stuck in the middle of Sudan with a giant, immobile tractor?

No doubt, Tewolde and I were mischievous. But we weren’t nearly as dangerous as our friend Kiros. He was only six but could climb any tree, no matter how tall. Fifty feet. Sixty feet. One hundred feet! No problem. And he loved stones. So he would climb trees with stones in his pocket and pick off whomever passed by.

All of us made room for him at our tables, knowing that with one stone, he could take our eyes out. Even the old woman who peddled peanuts next to the clinic shared her wares with him.

After two years, Kiros left Umsagata for a faraway paradise. I think his dad called it Ameri

kha

.

Kiros’s stones, while frightening, were hardly the most dangerous part of camp life. Famine always threatened, war raged nearby, and disease took its toll. Many refugees died from sickness, and at one point, a deadly disease called

kala-azar

invaded my body. Neither food nor rest nor medicine seemed to help. I remember approaching death and being carried around at night, through the dusty roads and thatched adobes of our own village, through the solemn silence of the neighboring Muslim village.

With time, though, my body recovered.

On days such as my recovery day, or on religious feasts, all the

habesha,

or Ethiopian and Eritrean people, in our camp celebrated together. We danced our people’s circle dance, moving our shoulders emphatically to the steady beat. We used no synthesizers or elaborate drum sets — just a goat-hide drum and a goat-hide guitar.

To the best dancers went more than admiration. Spectators moistened bills and slapped them enthusiastically on the best dancers’ heads.

My father knew how to dance with every muscle in his body — shoulders, arms, hands, back, knees, feet, legs. Even his face gyrated in perfect rhythm with the drum and the guitar.

Villagers always interrupted their business when he joined the dancers’ circle. Conversations stopped. Cups were lowered. Heads turned. Then the villagers jumped from their seats and plastered him with money, until bills decorated his head, his neck, and even his clothes.

He was hands down the best dancer in our village — the best dancer of

habesha

music that I have ever seen. Years later in the States, when my father had lost much of his eyesight and co-ordination, my

habesha

friends would still watch him in wonder. “If I could dance like that,” they would say, “I wouldn’t need anything else. Women would just drop at my feet.”

When the dancing finished, we would return to our one-room adobe, where my entire family slept. My mother, who knew how to scare young children into proper behavior, always old me that if I let the covers down, snakes could slither into my mouth and enter my body. She said that it had happened to little boy in our neighboring village.

I believed her and started pulling the covers over my head, still do it today.

Unfortunately, my family had much more to fear than imaginary snakes. Sudanese rebel groups waged their own war against the Sudanese government, and though the fighting never reached our camp, the Sudanese armies were always looking for new soldiers. They didn’t hesitate to draft refugees.

We also didn’t know how long we could dodge the diseases at had conquered so many of our countrymen.

One thing was certain: We could not seek safety in our homeland of Ethiopia. The Eritrean liberation groups continued their quest for independence and were joined by other Ethiopian liberation forces. If we returned home, my parents believed, we would be wiped out by the rebel group or by the Dergue army of Ethiopian dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam.

So it was that my father started talking about a paradise called Ameri

kha

, a distant land where everyone had a future. He told us that money grew on trees in Ameri

kha

. Everyone was rich. Everyone had a home. Everyone had food. And everyone had peace.

Everyone lived to be one hundred years old. And had access to free education. And no wars — no wars! Yes, everyone had cars, and no one had to work more than two hours a day.

What a country! What a paradise!

But such a faraway paradise included no relatives, no friends, and no one who spoke our language. Some villagers encouraged my parents to go; others begged them to stay.

“Have you lost your mind, Haileab? Don’t you care about your children? Don’t you care about yourself?”

“Don’t believe all the stories, Tsege. You will be lost if you go there. You and your children will be lost. You’ll end up washing their mules and other livestock.”

“Go, Haileab. Don’t listen to them. Go, and take your family with you. Even if you remain poor, your children will become educated, and at the very least, you will have peace.”

Would you go to paradise if it meant knowing no one? Would you give up everything you had ever known?

The day came when my parents had had enough. War at home. War in Sudan. My parents wanted peace, and they were ready to go. The village elders watched them and offered a few words of wisdom.

Heading to America, are you? They say that everyone there drives big cars and lives in big houses. Money flows through streets of glimmering gold. And everyone lives long, easy lives.

You will undoubtedly be happy there. Go well, live long, and please, do not forget us.

But as you gather your belongings, please permit us a few words of caution. We may be the poorest and least educated of folks, Ethiopian and Eritrean refugees living in Nowhere, Sudan, but even we have heard things that may interest you.

America seems sweet on top, like fresh honey straight from the comb. But what’s sweet on the surface is often rotten underneath. So beware.

Beware your skins. Blacks are treated like

adgi

in America, like packhorses. Beware, too, of thieves. Yes, thieves who steal much more than money — thieves who can loot minds, cultures, and even bodies.

Most of all, please remember your country and remember us. Remember your people.

My family in Khartoum, Sudan, right before we came to America. From left to right: Top: Mulu, Tsege, Haileab; Bottom: Selamawi, Mehret, Tewolde.

OMING TO

A

MERICA

M

y parents couldn’t just snap their fingers and conjure up a transatlantic jetliner. They needed help, so they contacted World Relief, a U.S.-based Christian organization that located refugees and helped them resettle in the United States.

Millions of my people had become refugees during the thirty-year bloodbath between Ethiopia and Eritrea. Most had fled to Sudan. Seeing their plight, World Relief had mediated an agreement between the United States and Sudan to resettle some of the refugees.

As part of the resettling process, World Relief would have to identify American sponsors who would find the refugees housing, furniture, jobs, medical treatment, and schools — everything that they would need to get on their feet.

But before a family could qualify for resettlement, it had to pass the infamous tests. No one knew which answers were right and which were wrong.

“Why do you want to go to America? What will you do when you get there? Do you want to come back to your country someday? Do you plan to work in America?”

Many clever interviewees had failed despite giving the same answers as those who had passed. Others had passed after giving the same answers as those who had failed.

My family hadn’t even gotten to the interview room when my father’s booming voice stopped the rest of us in our tracks. DON’T ANY OF YOU SAY A WORD OR I WILL MAKE YOU LOST. LET ME DO ALL THE TALKING.

Apparently, he told the officials what they wanted to hear, and they told us what we wanted to hear: “You are going to America! To a city called Chicago.”

We would have left for the States in 1982. We had already passed the infamous immigration tests, sold our six goats, and begun to say good-bye to our fellow villagers. But in the final days, right before we were to leave our village forever, my half sister Mulu came from another region of Sudan, surprising us.

Although we were scheduled to depart in a matter of days, my father and mother refused to leave without her. They begged the immigration officials. Y

OU HAVE CHILDREN, DON’T YOU?

W

OULD YOU GO TO

A

MERICA AND LEAVE YOUR DAUGHTER ALONE IN THIS REFUGEE CAMP?

“Look,” they told us, “World Relief agreed to work with a family of five, not a family of six. They agreed to bring you now, not later, and it’s impossible for her to come with you now. She has no paperwork.”

But my parents refused to leave her. Returning day after day, sometimes three times a day, my father wore down the officials until they finally caved in. She could come if we waited one year.

We waited, the year passed, and in 1983 the six of us started on our way: my father, Haileab, in his late forties; my mother, Tsege, in her mid-twenties; my half sister, Mulu, in her late teens; my older brother, Tewolde, nine; my younger sister, Mehret, five; and me, Sclamawi, almost seven years old.

Our friends gathered around to bid us farewell and a truck rumbled toward us. It was a lorry, one of those mammoth vehicles that looks like an African elephant. Its gaping back entrance beckoned us, giving us advice. Oh, that we could have heard it!

Come on in. Come, if you dare.

Make your choice carefully, for once you enter, you cannot return.

Turn and look at your friends, and know that they are your true family. For friends and even enemies become family when you live in exile.

Look at them and know that you will never see them again. Wave good-bye to H. Go hug him.

Believe it or not, you will miss even the bullies and the cruel math teachers. For even the most horrifying memories are you; they are yours and no one else’s. And they, along with the good memories, are your life.

You know America through stories. You know it to be paradise. But beware! Rumors are malignant tumors. Snakes lurk even in paradise. And the advice of mothers does not always ward off evil.

Look back, too. You have survived many dangers. Famines. Diseases. Wars. Despair. Homesickness and more. Who knows what your future will bring?

We entered the lorry slowly. Behind us, our village waved, both happy and terrified for us. And for themselves, too. We waved good-bye, and the lorry rumbled off, a bloated country taxi, jam-packed with hopeful innocents.

We made our way through the Sudanese wilderness, up and down the hills, to Gedariff.

We spent several months in Gedariff. Then a week in the capital city, Khartoum.

Then we entered the plane and took off from Khartoum. Next stop, Athens. Then Ameri

kha,

and there, a new life.

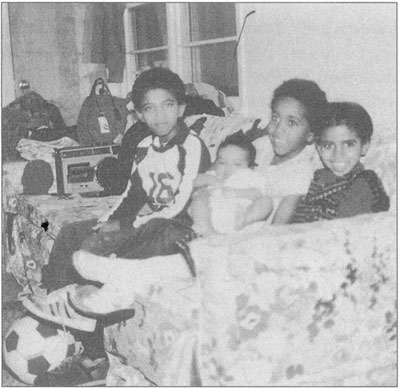

I’m holding the newest member of our family From left to right: Tewolde, Hntsa, me, Mehret.

EW

L

IFE

W

e spent our first two weeks in America in a two-room, two-bed motel room in Chicago, my parents on one bed, and on the other, all of us children.